The Consequences of Taking Greenland

Trump is determined to make Greenland part of the United States. The consequences for the United States—and the world—will be severe

When Saddam Hussein was quickly toppled by the swift military assault on Iraq in 2003, voices within and without the George W. Bush Administration raised an urgent question: “Who’s Next?”

The same hubris has now infected the Trump Administration. Trump has already issued warnings against Colombia (its president, he says, should “watch his ass”) and Mexico for its failure to curtail the drug cartels. But its Trump’s determination to take over Greenland that has raised the most immediate concerns.

The Threat to Greenland is Real

It’s been evident for more than a year that Trump has had his eye on Greenland, and that he was serious about making it part of the United States (as I argued before). In the days since the Venezuela operation, the president and his advisors haven’t minced words about their intention. “We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security,” Trump said on Sunday. Homeland Security Adviser Steven Miller told CNN, “it has been the formal position of the U.S. government since the beginning of this administration—frankly, going back into the previous Trump administration—that Greenland should be part of the United States."

It has been the formal position of the U.S. government since the beginning of this administration—frankly, going back into the previous Trump administration—that Greenland should be part of the United States.

On Tuesday, Secretary of State Marco Rubio reportedly told Congress that an invasion wasn’t imminent, but that the threat to do so was designed to force Denmark into a negotiation to sell Greenland to the United States. The White House followed suit with a statement:

President Trump has made it well known that acquiring Greenland is a national security priority of the United States, and it’s vital to deter our adversaries in the Arctic region. The president and his team are discussing a range of options to pursue this important foreign policy goal, and of course, utilizing the U.S. military is always an option at the commander in chief’s disposal.

Denmark—and Europe—React

Denmark’s government has reacted with strong words to these various statements. Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen has repeatedly stated that Greenland is “not for sale.” Addressing the United States “very directly,” Frederiksen on Sunday said “it makes absolutely no sense to talk about the need for the United States to take over Greenland. The United States has no right to annex any of the three countries in the Commonwealth.”

European leaders have reacted more cautiously, refusing to focus on the threats emanating from Washington and underscoring their support for Denmark instead. Stressing that the “Kingdom of Denmark – including Greenland – is part of NATO,” a joint statement by European leaders issued on Tuesday insisted “Greenland belongs to its people. It is for Denmark and Greenland, and them only, to decide on matters concerning Denmark and Greenland.”

What’s at Stake?

The US threat to Greenland is real and unmistakable. Trump isn’t bluffing. He believes that the military’s success in Venezuela (and before that, against Iran’s nuclear program) gives him the power to do what he wants. And he’s wanted Greenland for a long time. Taking Greenland won’t be difficult. Its population of 50,000 won’t be able offer much resistance, nor will Denmark want to enter a fight it cannot win.

But—and there is a big “but”—that doesn’t mean that doing so is wise or cost-free. To the contrary, even the threat of taking Greenland raises profound issues about transatlantic relations and the future of NATO.

The argument Trump and his aides are making—that US security and deterring threats in the Arctic requires that it owns Greenland—is not only pernicious but fundamentally undercuts NATO’s foundation. As a part of NATO, the United States is already committed to defending Greenland from an armed attack. The Arctic region is home to seven nations—six of whom are members of NATO—and the Alliance has made Arctic security a central plank in NATO. To suggest that American security in the Arctic requires that it owns Greenland implicitly indicates that the NATO security commitment is hollow and insufficient for its security. That’s hardly a reassuring message to the other 31 NATO members, many of whom face far more immediate threats than the United States.

The Trump argument is especially ironic on a day when the leaders of Ukraine, Europe, and the United States agreed to legally-binding security guarantees for Ukraine in the event of a ceasefire in Russia’s war against Ukraine. How can Ukraine count on a United States that believes real security can be achieved only for those areas that form part of US territory? It makes a mockery of the entire idea of US security guarantees for other nations.

What Europe Can Do

While neither Denmark nor Europe can prevent a takeover of Greenland by the United States if Trump is determined to embark on such a course, they can make the move very costly for the United States. Rather than reiterating that Greenland is not for sale and its future is to be determined by Denmark and Greenland alone, Europe should set out the actions it is prepared to take—notably on trade, technology, and offering their territory for US military operations.

On trade, it is important to remember that the European Union was willing to swallow the unilateral imposition of a 15-percent across-the-board US tariff on their exports as the price to pay for continuing the US commitment to their security and to Ukraine. As António Costa, President of the EU Council put it,

We certainly do not celebrate the return of tariffs. But escalating tensions with a key ally over tariffs, while our Eastern border is under threat, would have been an imprudent risk. Stabilizing transatlantic relations and ensuring U.S. engagement in Ukraine’s security has been a top priority.

But once the US calls those commitments into question, which its threats to Greenland certainly do, making clear that Europe is prepared to impose its own tariffs on US exports at a rate equal to any US tariffs on European exports, would be one way to impose significant costs on the United States. After all, Europe remains the largest export destination for US goods, and exports have been rising significantly following the conclusion of the trade deal last summer.

On technology, Europe and the United States have long been at logger heads, especially with European digital regulations imposing meaningful constraints (and fines) on US technology companies. Strict implementation of the Digital Market and AI Acts would impact the extent to which US tech companies can extend their business model to Europe. At the same time, Europe will have an even greater incentive to develop its own technology stack, by encouraging investment in European startups, bolstering European chip design and production, and minimizing reliance on US cloud, cyber, and space-based assets.

Finally, while Europe is dependent on the United States for its security and defense, the US military is also very dependent on access to European bases, ports, airspace and waters. US operations in Afghanistan and Iraq earlier this century depended a great deal on redeploying capabilities form Europe to the Middle East. More recently, the US ability to help defend Israel against Iranian missiles and its attack on Houthis were enabled by US forces based in the Mediterranean and Britain. The strike against Iran nuclear targets last June required support from some 140 refueling aircraft and tactical aviation based in Europe. The B2 bombers that dropped the bombs on the nuclear facilities simply couldn’t have executed the mission without the refueling and other support based in Europe.

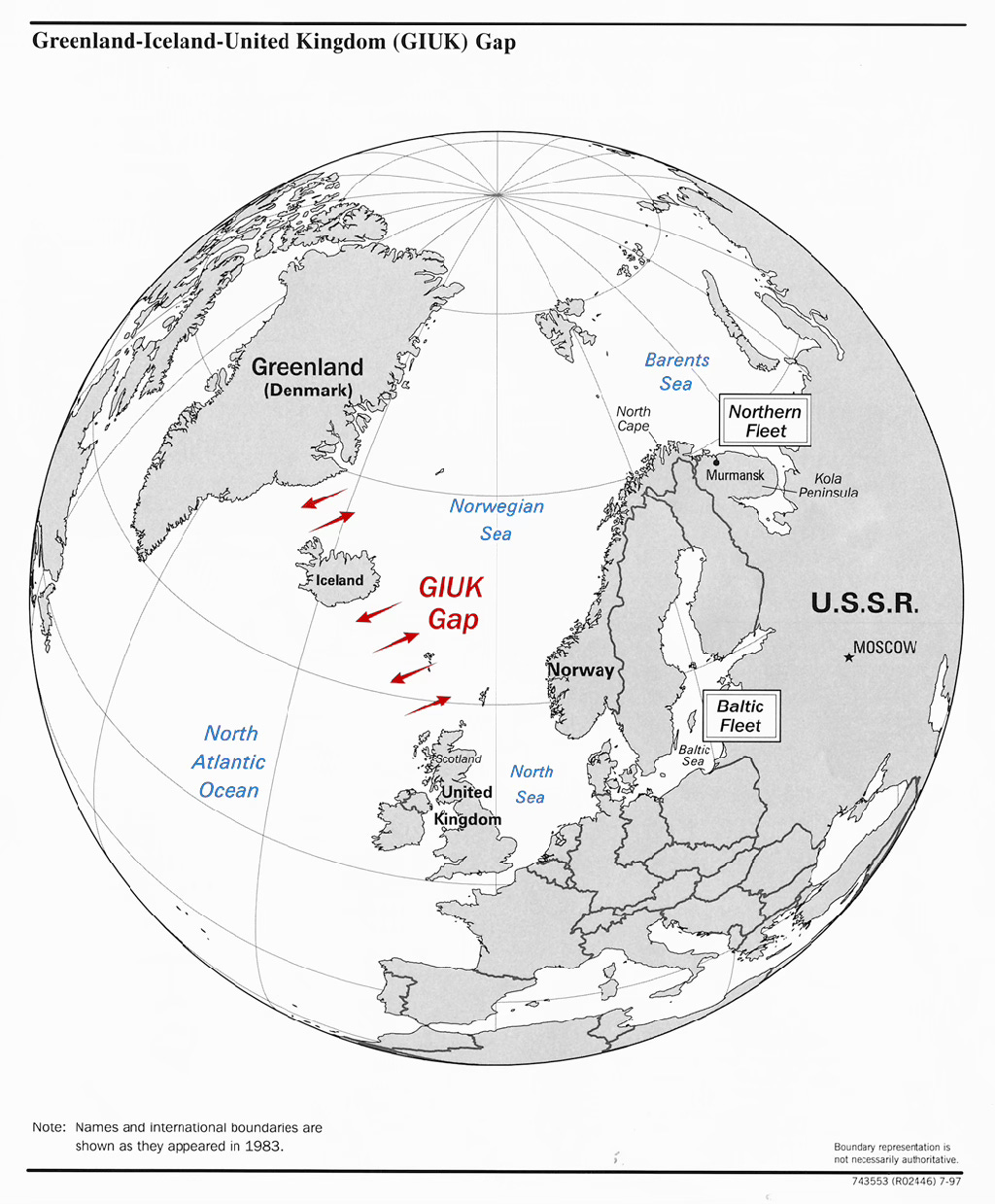

The defense of the US itself is also critically dependent on Europe. Most of Russia’s nuclear ballistic missile submarine fleet is based in Murmansk on the Kola Peninsula. To enter the wide reach of the Atlantic, these submarines have to transfer narrow channels between Greenland, Iceland, and the UK. Without active cooperation of Europe allies or access to the arrays and other equipment in these European states, finding Russian nuclear subs will be that much more difficult.

While the US can threaten the security of European members of NATO, Europe needs to make clear that its support for US military operations cannot be automatically assumed.

Two Can Play the Game

The United States under Donald Trump has returned to the old-fashioned game of power politics. Here is how Steve Miller explained that game to CNN’s Jake Tapper: “We live in a world, in the real world, Jake, that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power,” he said. “These are the iron laws of the world since the beginning of time.”

Faced with this reality in the case of Greenland, Europe now needs to understand—and make Trump understand—that in the game of power politics, two can play the game. Europe has much to bring to that fight. The consequences will be costly for everyone. But it’s price that may well have to be paid to demonstrate the true folly of Trump’s hubris and misplaced ambitions.

Might it be asking too much for some Republicans in Congress to finally grow a backbone and try to curb Trump’s imperialist tendencies?

It would be pretty hard to maintain a fleet in the Med if all those ships need to return to Norfolk to refuel and reprovision.

Europe needs to accept reality. America is no longer the good guys. It is more likely that the US will attack Europe than defend Europe from attack. Behave accordingly. As soon as is practical seperate yourselves economically and in security from the US.